The untold story from Uttarakhand by Ravi Chopra (Excerpt from 'The HINDU')

The impact of the floods on Uttarakhand’s tourism leads to larger

questions of what kind of development Himalayan States should pursue.

Before delving into that, it is important to understand the nature of

the rainfall that deluged the State. Already several voices are arguing

that the deluge is a random, ‘freak’ event. Odisha’s super cyclone in

1999, torrential rains in Mumbai in 2005, and now the Uttarakhand

downpour constitute three clear weather related events in less than 15

years, each causing massive destruction or dislocation in India. These

can hardly be called ‘freak’ events.

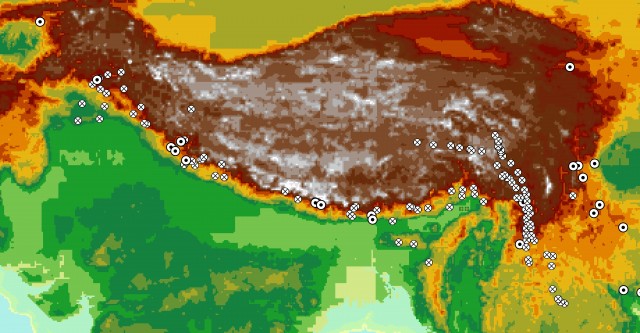

Several reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

(IPCC) have repeatedly warned that extreme weather incidents will become

more frequent with global warming. We are already riding the global

warming curve. We will have to take into account the likelihood of more

frequent extreme weather events when planning for development,

especially in the fragile Himalayan region where crumbling mountains

become murderous.

In the 1990s, when the demand for a separate State gained momentum, at

conferences, meetings, workshops and seminars, Uttarakhandi people

repeatedly described the special character of the region. Consciousness

created by the pioneering Chipko Andolan raised the hopes of village

women that their new State would pursue a green development path, where

denuded slopes would be reforested, where fuel wood and fodder would be

plentiful in their own village forests, where community ownership of

these forests would provide their men with forest products-based

employment near their villages instead of forcing them to migrate to the

plains, where afforestation and watershed development would revive

their dry springs and dying rain-fed rivers, and where the scourge of

drunken, violent men would be overcome.

Year after year — in cities, towns and villages — they led

demonstrations demanding a mountain state of their own. Theirs was a

vision of development that would first enhance the human, social and

natural capital of the State. Recalling the tremendous worldwide impact

of the Chipko movement, Uttarakhandi women dreamed of setting yet

another example for the world of what people-centric development could

look like.

But in the 13 years after statehood, the leadership of the State has

succumbed to the conventional model of development with its familiar and

single-minded goal of creating monetary wealth. With utter disregard

for the State’s mountain character and its delicate ecosystems,

successive governments have blindly pushed roads, dams, tunnels, bridges

and unsafe buildings even in the most fragile regions.

In the process, denuded mountains have remained deforested, roads

designed to minimise expenditure rather than enhance safety have

endangered human lives, tunnels blasted into mountainsides have further

weakened the fragile slopes and dried up springs, ill-conceived

hydropower projects have destroyed rivers and their ecosystems, and

hotels and land developers have encroached on river banks.

Yes, wealth has been generated but the beneficiaries are very few — mainly in the towns and cities of the southern terai

plains and valleys where production investments have concentrated. In

the mountain villages, agricultural production has shrivelled, women

still trudge the mountain slopes in search of fodder, fuel wood and

water, and entire families wait longingly for an opportunity to escape

to the plains.

Last week’s floods have sounded an alarm bell. To pursue development

without concern for the fragile Himalayan environment is to invite

disaster. Eco-sensitive development may mean a slower monetary growth

rate but a more sustainable and equitable one.

(The writer is Director, People’s Science Institute, Dehra Dun and Member (Expert), National Ganga River Basin Authority)

Praful Rao,

Kalimpong,

Darjeeling district.